The Thirteen-Day Shōgun

Akechi Mitsuhide’s coup d’état against Oda Nobunaga was arguably the defining moment of the late sengoku jidai. Had Nobunaga remained in power after 1582, the end of the century in Japan might have looked wildly different.

It remains a mystery what Nobunaga would have gone on to do had he not been consumed in the flames of Honnō-ji. Would the long-time friend of the Jesuits have started suppressing Christianity as his successors did? Would he have attempted the Korean campaigns of the 1590s? And how might he have reacted, aged nearly 66, when the Dutch ship Liefde limped towards Japan, carrying William Adams (Miura Anjin) and the secrets of English shipbuilding?

Considering this timeline, in which the distinct personalities of the three Great Unifiers loom large, Akechi Mitsuhide’s reign as ‘shōgun’ was a short but intense interlude. (Apocryphally, it lasted thirteen days, although it may have been eleven or twelve.) In this post, we will trace the twists and turns of Mitsuhide’s dramatic final act, which is set entirely in and around Kyoto.

The Scramble for Allies after Honnō-ji

Immediately after the Incident at Honnō-ji, Akechi Mitsuhide proclaimed himself shōgun and began petitioning the Imperial Court and various daimyō for recognition. While Hashiba Hideyoshi was stuck besieging Takamatsu Castle in Bitchū Province and Tokugawa Ieyasu was also occupied elsewhere, Mitsuhide hoped that enough supporters would flock to his banner to protect him from their inevitable retaliation. Some, in fact, may have promised their support prior to the coup itself. In the end, however, no daimyō were willing to put their necks on the line. In the tense days that followed, Mitsuhide rewarded his men by looting Nobunaga’s opulent Azuchi Castle, which burned down shortly afterwards.

Hideyoshi would be the first to avenge Nobunaga’s death. When the news reached him, he demanded a quick peace with the defenders of Takamatsu Castle (which he had flooded and bombarded almost into submission) and then force-marched his army back to Kyoto, leaving little time for Mitsuhide to prepare.

The Battle of Yamazaki

By Hideyoshi's arrival, Mitsuhide's forces had dwindled to as little as ten thousand men; this was half the size of Hideyoshi's army. He prepared to meet the larger force to the south of Kyoto, just short of the town of Yamazaki. There, the field of battle would be squeezed between two natural curves: the base of the wooded Tennōzan mountain and the confluence of the Katsura, Uji and Kizu rivers. What's more, a stream called Enmyōji-gawa ran down from the mountainside to join the main rivers, forming a natural obstacle across the battlefield. (Today it is a tiny brook overshadowed by a flyover.) Mitsuhide's army set up camp behind this stream, while Hideyoshi chose to control the high ground.

Some of Mitsuhide’s men attempted to cross the stream and assault Hideyoshi’s forward position on the mountainside, but they were pushed back by arquebus fire. In the end, Hideyoshi threatened to encircle the smaller force by advancing across Enmyōji-gawa on the opposite flank, which led to a general rout. Some of the Akechi forces put up a stand at Shōryūji Castle, which stood between the battlefield and the southwestern outskirts of Kyoto. However, they were again quickly overrun.

Mitsuhide's Ignoble End

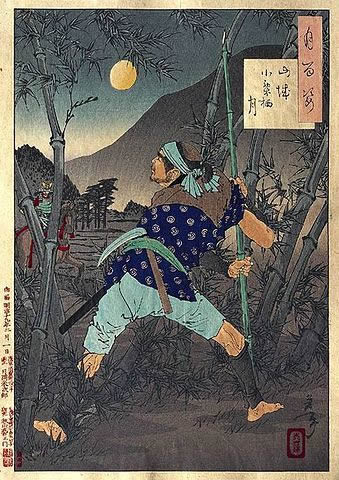

Mitsuhide fled, hoping to take refuge in Sakamoto Castle to the northeast. Unfortunately, since he now held the perilous status of ochimusha (‘fallen warrior’), the famed general was fair game for peasant bandits. After dark, near a village called Ogurisu, he was supposedly stabbed and killed by one such bandit wielding a bamboo spear.

Mitsuhide is enshrined today in a tiny alley in Umemiyachō, a quiet residential corner of Kyoto’s picturesque Higashiyama district. While this humble resting place might accurately reflect the significance of his reign as shōgun, it certainly understates his importance in the Japanese popular imagination. Since so little is known for sure about his true motivations, Akechi Mitsuhide remains the righteous underdog, treacherous villain and tragic rebel of the sengoku jidai rolled into one.