Luís Fróis: 16th Century Japan Through Foreign Eyes

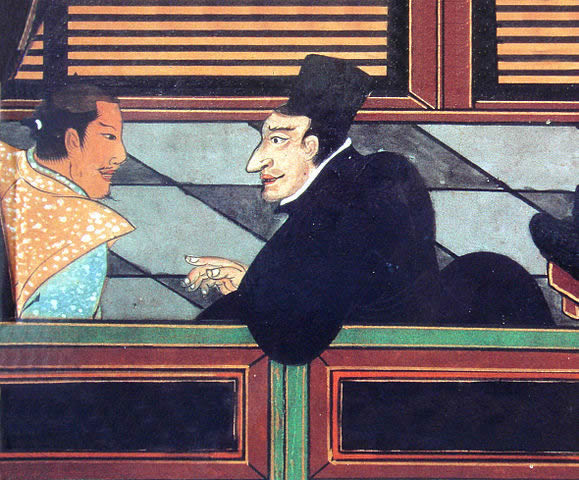

In the history of the sengoku jidai, there are a few interesting figures from outside Japan who cannot be overlooked. One of these is Luís Fróis, a Portuguese missionary and friend of Oda Nobunaga who is known for his vivid written descriptions of mid-16th century Japan from an outsider’s perspective.

What brought Luís Fróis to Japan?

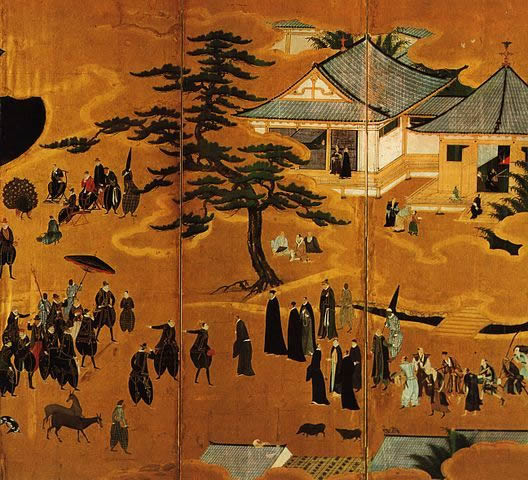

Luís Fróis was not the first European, or even the first Portuguese visitor to the islands of Japan when he arrived there in 1563. The first documented Portuguese visitors had set foot in Tanegashima some twenty years prior, bringing with them muskets which, quickly replicated, became an important tool in Japanese warfare. In the intervening years, a stream of traders were welcomed by various daimyō who recognised the strategic advantages of European technology. With them came Jesuit missionaries including Saint Francis Xavier, who established the first Catholic congregations in Japan

In the late 1540s, a young Luís Fróis joined the Society of Jesus in Lisbon and accompanied a handful of Jesuits headed for Goa, Portugal’s trading post in India. After transferring to Malacca for a few years, where he undertook various clerical duties, he returned to Goa and was finally ordained as a priest. From there he was sent as a missionary to Japan, where he quickly became immersed in Japanese culture and language. Since missionaries continued to play an important role in brokering trade and diplomacy, high-ranking Jesuits in Kyoto enjoyed privileged access to the great and the good of Japanese society.

In 1569, Oda Nobunaga even invited Fróis to stay at his grand residence in Gifu, which the priest described as a city of ‘so much traffic and trade that it looked like a Babylonian confusion.’

Writings on Japanese Culture

Despite many instances of culture shock, Fróis considered the Japanese a highly civilised and ‘reasonable’ people. This was high praise coming from a European of his time and vocation. In addition to extensive chronicles and reports, Fróis also wrote hundreds of cultural observations which he would later compile into a Tratado (treatise) on the differences between Europeans and Japanese. Here are a few of the more surprising examples:

- In Europe, boar are hunted on horseback with pikes, hounds and arquebuses; the Japanese often chase them swinging katanas.

- Among us, honoured individuals ride at the stern [of a boat]; in Japan, noble folk ride on the bow, where they sometimes get rather soaked.

- In Europe, baring one’s foot to a fire to warm it would be strange; in Japan, they are not ashamed to stand by the fire to warm themselves by openly baring their behinds.

While these images are as odd to us now as they were to Fróis, many other Japanese habits he described are still recognisable, from the removal of shoes indoors to the delight in cherry blossom, raw fish and ‘ambiguous’ polite language.

Later Years in Japan and Legacy

Oda Nobunaga had been a friend and patron of the Jesuits throughout Fróis’s career. The Chancellor of the Realm even overruled neighbours’ complaints to permit the building of Kyoto’s first three-storey church in 1576, just as Fróis was preparing to hand over to a new head of mission. The bell of Our Lady of the Assumption, also known as Nanban-ji (literally, ‘southern barbarian temple’) survives to this day.

Oda Nobunaga had been a friend and patron of the Jesuits throughout Fróis’s career. The Chancellor of the Realm even overruled neighbours’ complaints to permit the building of Kyoto’s first three-storey church in 1576, just as Fróis was preparing to hand over to a new head of mission. The bell of Our Lady of the Assumption, also known as Nanban-ji (literally, ‘southern barbarian temple’) survives to this day.

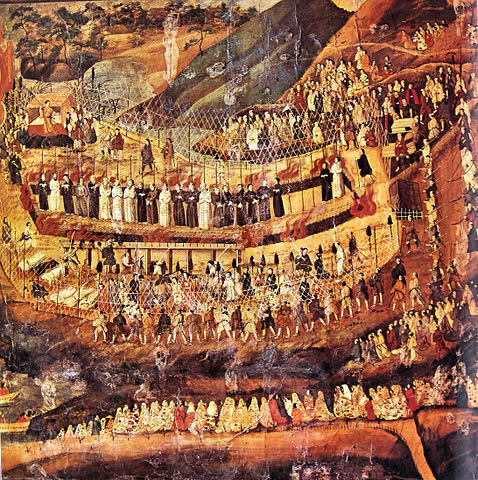

Despite subsequently moving to Kyushu, Fróis records witnessing the Incident at Honnō-ji first-hand in 1582. As it happened, he was temporarily back in Kyoto to cover his old post. If Nobunaga’s death was not shocking enough, Fróis would yet see the persecution and suppression of Christianity under Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Indeed, one of the last events he would chronicle before his own death from illness in Nagasaki in 1697 was the crucifixion of the 26 Martyrs of Japan in that same city.

His extensive writings and correspondence remain a crucial historical source on the heyday of Japan’s so-called ‘Christian Century’ and a fascinating window on Japanese culture of the time.