How Oda Nobunaga Became the Great Unifier

Oda Nobunaga is remembered as the first Great Unifier of Japan. But from his father ’s death in 1551 until 1560, he had mainly fought to maintain his own position as a regional warlord. The Battle of Okehazama, in which a guerilla-like stratagem won the day for Nobunaga against a numerically superior foe, marked a significant turning point in his ambitions. In the years that followed, Nobunaga resolved to conquer the whole country piece by piece. For twenty years, he succeeded - until an unexpected betrayal put an end to his life.

Cast of Characters

The Great Unifiers

- Oda Nobunaga, head of the Oda clan

- Matsudaira Motoyasu, later Tokugawa Ieyasu

- Kinoshita Tōkichirō, later Hashiba Hideyoshi (better known as Toyotomi Hideyoshi)

Ashikaga Shogunate

- Ashikaga Yoshiaki, 15th and final shōgun

- Ashikaga Yoshihide, his infant cousin and 14th shōgun

Others

- Saitō Yoshitatsu, hostile neighbour of Nobunaga

- Takeda Shingen, powerful daimyō from Kai Province

- Akechi Mitsuhide, Nobunaga's general and ultimate betrayer

The First Expansion Beyond Owari

Having literally decapitated the Imagawa threat at the Battle of Okehazama in 1560, Nobunaga proceeded to secure his eastern borders through new alliances. Perhaps surprisingly, this included an alliance with the former Oda and Imagawa hostage, Matsudaira Motoyasu, who was beginning to reassert his clan's independence.

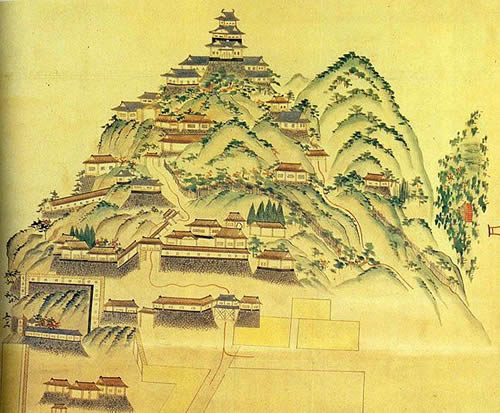

The sudden death of Saitō Yoshitatsu, Nobunaga's neighbour to the north, provided an excellent opportunity for expansion into Mino Province. Nobunaga and his generals, among them the lowborn rising star Kinoshita Tōkichirō, managed to progressively undermine support for the Saitō clan. The capture of Inabayama Castle in 1567 was the final coup de grâce; the strategic moun-tain fortress was renamed Gifu Castle (a name with grandiose Chinese overtones) and the general responsible for its capture, Tōkichirō, was renamed Hashiba Hideyoshi. This would become the new centre of Oda power.

The End of the Ashikaga Shogunate

Meanwhile, all was not well in the capital. The Ashikaga bakufu had been without a figurehead since 1565, when the 13th shōgun died in a coup. His brother, Ashikaga Yoshiaki, had naturally fled. Finally, in 1568, their infant cousin Ashikaga Yo-shihide was named shōgun in a blatant power grab by his would-be regents.

Ashikaga Yoshiaki turned up in Gifu to beg Nobunaga for his support in retaking the throne. The Oda clan leader needed little encouragement to battle his way to Kyoto, make Yoshiaki his very own puppet shōgun, and bring the conspirators to heel. It turned out in any case that they had backed a losing horse; the unthroned Yoshihide soon died of an infectious disease.

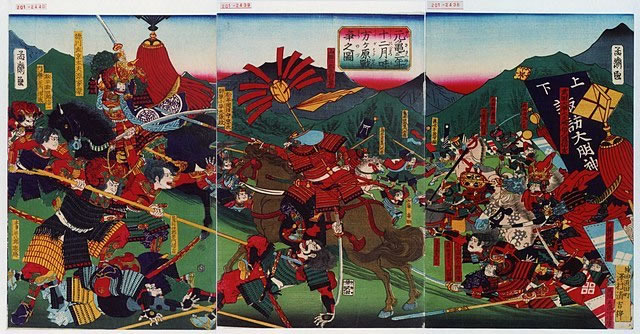

For the next five years Nobunaga battled a medley of opponents. Some of these were encouraged by Yoshiaki, who resented his lack of independence as shōgun. However, they were for the most part brutally crushed. Perhaps the most dangerous among them, Takeda Shingen, threatened to overrun the forces of Matsudaira Motoyasu, who was by now styling himself Tokugawa Ieyasu.

In 1573, however, Shingen died, allowing Nobunaga to turn his attention once again to Kyoto. By forcing the recalcitrant Yo-shiaki into exile, he finally disposed of the impotent Ashikaga bakufu and signalled to the other daimyō that supreme military rule would be his alone. The Imperial court appeased this new warlord in the usual way, showering him with increasingly mag-nificent titles.

The Honnō-ji Incident

While Nobunaga was well on the way to uniting the whole of Japan, opposition to his rule persisted in various parts of Honshu. In particular, he would be forced to continue fighting the Takeda (under new and largely inept leadership) until the final year of his life. The Mōri clan of western Honshu also put up significant resistance; in fact, it was while Hashiba Hideyoshi was be-sieging them at Takamatsu Castle, Bitchū Province, that Nobunaga was struck down in a surprise betrayal.

Nobunaga was touring Kansai when a request came from Hideyoshi for reinforcements. He ordered his trusted general Akechi Mitsuhide (once a Saitō retainer and then a servant of Ashikaga Yoshiaki) to move on Bitchū, gathering forces on the way. Meanwhile, Nobunaga stopped with a small retinue at Honnō-ji temple in Kyoto.

The real motive for what followed is unknown. Mitsuhide may have acted on a personal grudge or out of fear for his own posi-tion; he may have harboured more principled objections to Nobunaga's rule; or he may have been manipulated by others. What-ever the true reason, Mitsuhide raised his men, declared, 'The enemy is at Honnō-ji!' and turned back to Kyoto, catching Nobu-naga virtually undefended. Surrounded and unable to hold off Mitsuhide's men, Nobunaga committed seppuku. He also had the temple set ablaze, preventing his remains from being paraded, or indeed found.

Mitsuhide's coup was short-lived. A matter of days after the Honnō-ji Incident, he was defeated at the Battle of Yamazaki and killed while fleeing across Kyoto. While he is sometimes written off as a jealous minor figure of the sengoku jidai, un-doubtedly the course of Japanese history might have been very different without his actions. In reality, the late sengoku jidai would be dominated by the efforts of Hashiba Hideyoshi (who would acquire the clan name Toyotomi) and Tokugawa Ieyasu to follow in Nobunaga's footsteps and achieve his dream of total power.