Who was Toyotomi Hideyoshi?

Toyotomi Hideyoshi is known as the second of the three Great Unifiers. Although he came from an obscure background, his martial prowess and negotiating skills made him an indispensable factor in Oda Nobunaga’s rise to virtual dictatorship of Japan. Despite having no natural claim as Nobunaga’s successor, Hideyoshi managed to manoeuvre himself into power in the wake of the Honnō-ji Incident. As Japan’s political and military overlord, he completed Nobunaga’s subjugation of the recalcitrant daimyō and laid the foundations for the reinforced social order of the Tokugawa period.

Origins and Early Career

Little is known for certain about Hideyoshi’s early life; he served various lords as a lowly soldier before coming to prominence in the army of Oda Nobunaga. His first step towards greatness was the capture of Inabayama Castle in 1567, which concluded Nobunaga’s campaign to control Mino Province. Following that victory, Nobunaga gave Hideyoshi a minor lordship and the name Hashiba Hideyoshi.

As one of Nobunaga’s most trusted and effective generals, Hashiba Hideyoshi took part in many important battles and sieges. At the time of the Honnō-ji Incident in 1582 he was commanding a large force in Bitchu Province, which he was quickly able to bring to bear against the upstart Akechi Mitsuhide. Being the first on the scene to counter Mitsuhide’s coup boosted Hideyoshi’s already significant power and influence.

Hideyoshi's Consolidation of Power

The Honnō-ji Incident had wiped out both Nobunaga and his eldest son, Nobutada. This triggered a succession dispute between the next two Oda sons, Nobukatsu and Nobutaka, who were both aged around 23-24. Hideyoshi, ever the strategist, used his influence to settle the matter in the time-honoured fashion: by backing a compliant infant candidate instead. Nobutada’s son Sanbōshi duly became Nobunaga’s official heir, while Hideyoshi held the reins of power.

This solution was not accepted peacefully. Nobutaka had to be ruthlessly eliminated and Nobukatsu brought to heel before Hideyoshi could cement his position. By 1586, however, Hideyoshi had taken not only a grand new surname, Toyotomi, but also the titles of Imperial Chief Advisor (kampaku) and Chancellor of the Realm. Newly legitimised, he set about the consolidation of central rule. By the end of 1590, he had taken Kii Province, Shikoku, Etchu Province, Kyushu, and finally the lands of the Odawara Hōjō clan. With this, he effectively brought the ‘Age of the Country at War’ to an end.

Leaving his Legacy

Hideyoshi’s final years were defined by the idea of overseas conquest - another dream inherited from Nobunaga. Since Joseon would not allow Japanese armies to pass through its lands to attack Ming China, the Korean kingdom itself became the target of a preliminary invasion in 1592. The Imjin War, as this drawn-out struggle became known, ultimately ground to a stalemate. Upon Hideyoshi’s death from illness in 1598, Japanese troops were withdrawn from the Korean peninsula.

As for the development of Japanese civil society, several of Hideyoshi’s acts would resonate long after his death, for example:

- The anti-Christian edicts of 1587, which limited freedom of conversion among landowners and expelled foreign missionaries.

- The Separation Edict of 1591, which prevented members of the samurai and field-labouring peasant classes from taking up other professions.

- The Population Census Edict of 1592, which ordered a complete account of Japan’s production and military potential.

The Fall of Toyotomi and the Rise of Tokugawa

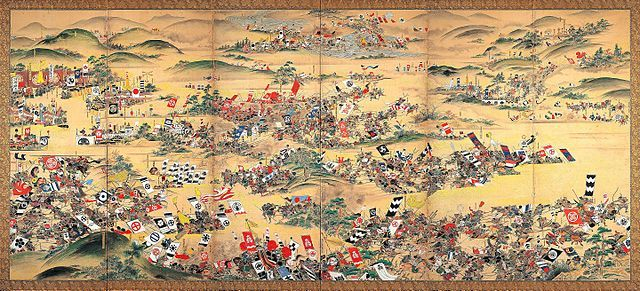

By transferring favour to his son Hideyori just five years before his own death, Hideyoshi had inflicted yet another child heir debacle on his own would-be dynasty. Two years of wrangling among the boy’s regents culminated in the epochal Battle of Sekigahara, from which Tokugawa Ieyasu emerged victorious.

The hereditary bakufu established by Ieyasu after Sekigahara would last two and a half centuries. During this time, Japan would attempt no more foreign invasions. Instead, the largely peaceful Tokugawa period was characterised by urbanisation, a strict class system (built on the foundations laid by Hideyoshi) and - most of all - the isolationist foreign policy which began under Ieyasu’s grandson.

Like Nobunaga before him, Hideyoshi is reviled today for his brutality as much as he is admired for his ambition. In the end, however, this ambition was partly to thank for Japan’s emergence from the bloody chaos of the 16th century.